Digest of the session "The Science of Gel, a Fusion of Different Fields, Begins" at the Tokyo 2025 Conference of the Association for Transdisciplinary Research.

2025.12.29The Challenge of "Complex Gels" to Update Gel Science

The ERATO Sakai Complex Gels Project, launched in October 2024 by Professor Takamasa Sakai of the Graduate School of Engineering at the University of Tokyo, aims at a comprehensive understanding of general polymer gels based on the foundation of gel theory derived from tetragels, which allow precise control of microscopic network structures developed by Sakai and his colleagues. Not only that, we are also trying to expand our understanding to materials and populations with networking properties by considering abstract gels as the abstraction of knowledge about networking properties, etc., obtained from gels as materials (concrete gels).

Discussions that included researchers participating in this initiative were held at the Association of Hyperdifferent Fields Tokyo 2025 in March 2025. Here is a digest of the session.

---------------------------------

speaker

Professor, Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo

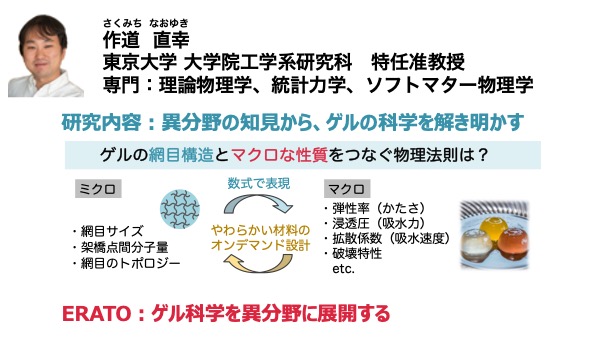

Naoyuki SakumichiThe University of TokyoGraduate School of Engineering Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Specially Appointed Associate Professor/Currently Associate Professor, ZEN University (concurrent position))

Zou Masuda (Assistant Professor, Department of Bioengineering, Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo (at the time of the session)/present)The University of TokyoGraduate School of Engineering Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering specially-appointed lecturer)

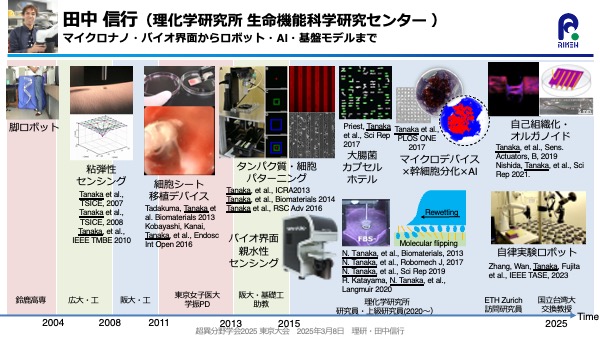

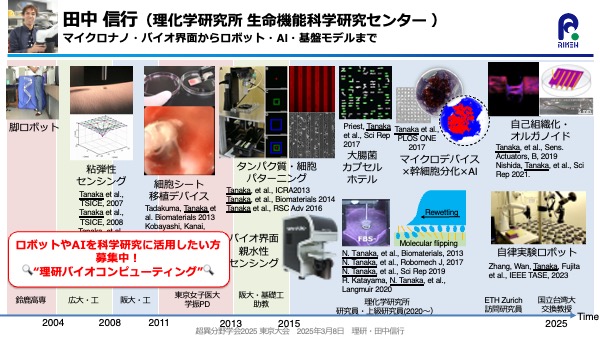

Nobuyuki Tanaka (Senior Engineer, RIKEN Center for Frontier Biosciences)

moderator

Hiroyuki Takahashi (Director, Knowledge Foundation Research Center, Liverness Corporation)

---------------------------------

Start of a major project in gel science!

Takahashi:Yes, hello everyone.

You have all probably heard the word "gel" at least once at some point.

Today, I would like to join with you in the new world of gel research that Mr. Sakai and his colleagues at the University of Tokyo are trying to set up, which could change the way you imagine the world of gels.

Takahashi:Mr. Sakai of the University of Tokyo, Mr. Sakumichi of the University of Tokyo, Mr. Masuda of the University of Tokyo, and Mr. Tanaka of RIKEN will be invited, and I, Takahashi of Livanes, will be the facilitator.

Best regards.

Takahashi:Now, I would like to ask you all some questions as a warm-up.

Takahashi:I am putting on the screen what I have researched and come up with regarding gels, and I see that jelly and tofu are gels. And konjac.

Then there are sausages, ham, and eggs.

In today's keynote speech, Mr. Sakai said that onigiri is also a gel.

Takahashi:I have never heard of silica gel before, but it seems that silica gel is also broadly classified as a gel.

Takahashi:I think that most people have a strong image of gel as being jelly or agar, but I first learned that many other things can also be classified as gel.

Takahashi:I would then like to ask the audience and the speakers to raise their hands to see which of these would be the ger, and I would like to know first how much of a difference there is in perception.

Takahashi:First of all, it's a wrap.

How many of you believe that wraps are gels?

One, two, and this is pretty much a split among the speakers.

Takahashi:Next, plastic containers.

How about this?

Does anyone think this is a gel?

There is one person here.

Two in the back.

This is also divided among the speakers, so I would like to ask Dr. Sakai later.

Takahashi:How about jellyfish?

It is starting to feel like you are all gels, partly because this place is quite squishy. So what about humans?

Takahashi:Yes, thank you for taking the time to warm up.

Mr. Sakai raised his hand when asked earlier whether rap is a gel, but the audience was quite divided in their answers.

Here, I would like to ask Mr. Sakai what he considers a gel.

Sakai:If it is solidified, it is like a gel, but if the polymer has a mesh-like structure, it can be called a gel.

This time, the content is called Gel for everything.

Now I have to list them all. (Laughter)

But we are about to start research that will expand the idea of gel to such a point.

Takahashi:Yes, thank you.

Including the points you just mentioned, Mr. Sakai, could you introduce yourself and tell us a little about what it is like to be a GER?

Sakai:Hello, my name is Sakai. Pleased to meet you.

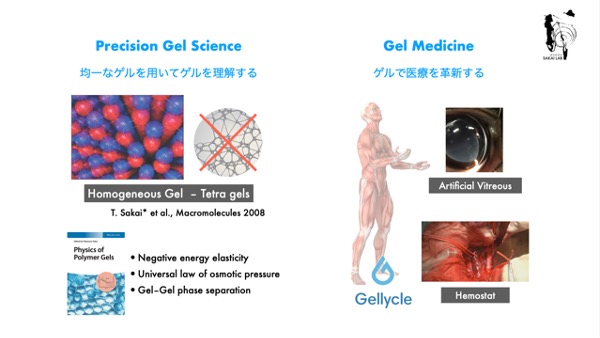

Sakai:One is the understanding of gel as a material.

It is typical for a network of polymers to contain water to be called a gel, but I would like to understand the material of gel properly.

It is my one life's work.

Sakai:The other is trying to make something really useful with gel.

We are developing artificial vitreous, hemostatic agents, and other so-called medical devices with the aim of innovating medical care from this perspective.

Sakai:This is the first half of your understanding of gel as a substance.

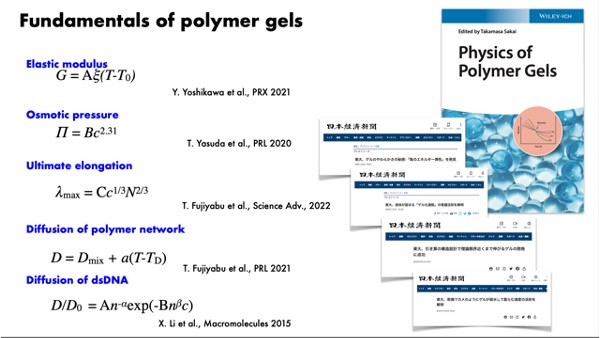

The formulas are all lined up, but the point is to understand exactly what formulas relate to gel structure, gel hardness, gel water holding capacity, etc. This is one of the tasks of this project.

Sakai:As for the other medical device, of course we make the skills.

I thought about how we could use this kind of thing, and then built it in,

We discuss with these doctors what kind of knowledge they have and what kind of needs they have, and then we build it into a medical device.

Still, it was quite a challenge, and I decided to do a social implementation.

I started a venture to fill that gap, and I am also the CSO there.

Takahashi:Thank you very much.

Gel, very roughly speaking, is a net-like structure made up of string-like objects connected to each other. I guess that's about the size of it.

Sakai:And if it is scanty, it is even better.

So is Jell-O.

In the case of the jellies that are usually eaten, about 2% is string and 98% is water.

Water accounts for almost 98% of the total.

In that sense, it is a scuzzy gel.

Takahashi:Also, earlier you mentioned something like porous or aerogel.

That does not have water in it, but if the substance has a network structure, does that mean it is a gel?

Sakai:Yes, it is.

Gel is like that, and aerogel is a pattern that contains gas.

Organogel contains organic solvents.

The name changes slightly depending on what's in it, but that's how the gel is.

Takahashi:Also, gel is elastic, like it can be shrunk and put back together.

Where does this characteristic come from?

Sakai:Basically, there is a grid of strings in the gel.

For example, in jelly, but also in rubber.

Actually, the gel is full of polymeric strings that are twisting and turning and moving.

Thermal exercise.

Sakai:Because it is a net, it can be stretched when pulled.

The string is in a squishy state by default and folds as it moves.

When you are pulling a gel, you are pulling a string.

When the string is undone, the entire net is folded.

This is the source of the gel's elasticity.

The default state is the squishy state when the folded state is thrown against a wall.

Takahashi:It is important that the string is not straight and pinned, but rather random.

Takahashi:Well, we started this issue by talking about gels of any kind.

I understand that just yesterday (*March 7, 2025) there was a kick-off symposium for the project with the aim of opening up this new research area.

Sakai:Yes, a 5.5-year project called ERATO, which is related to JST, has just started in the fall of 2024.

This is its kick-off symposium.

Takahashi:We will challenge ourselves to expand the way of thinking about gels by having not only conventional gel researchers but also people from various fields come into this project.

Will it be such a grand project?

Sakai:Yes, it is.

Gels are generally found in the field of polymer chemistry.

So when you open a polymer textbook, there may or may not be a chapter on gels.

Sometimes it is not, and if it is, it is rather minor in polymers, being sneakily included in the chapter on rubbers and the like, or in the chapter on polymeric solutions.

I have always thought that gels could be more interesting if they were opened up to other fields rather than shining in polymers, even though they are a minor part of the polymer society.

Sakai:I realized something while working with Mr. Sakudo and his team, and I thought that there would be interesting developments if I tried to give full play to what I had realized, which led to the launch of this project.

Takahashi:Gels that have been on the periphery are coming to the mainstream.

So this is such an ambitious initiative.

Sakai:Yes, it is.

It's like Ger strikes back.

I feel like I'm about to step out of the macromolecular frame of mind.

Looking at Gel from a Physics Perspective

Takahashi:Thank you very much.

I understand that you and Mr. Sakumichi have made some new discoveries in your research together.

Sakudo:Thank you very much.

My name is Naoyuki Sakumichi and I am a Project Associate Professor in Sakai Laboratory at the University of Tokyo.

My specialty is theoretical physics, and I am currently working on statistical mechanics and soft matter physics.

Sakudo:Since coming to Sakai Lab, I have been working to unravel the science of gels using knowledge from different fields.

In particular, my strongest interest so far has been in what are the laws that link the network structure of gels to their macroscopic properties.

Sakudo:The gel called Tetra PegGel that Dr. Sakai created can change the structure of the microscopic network in various ways.

We know that this gel can be continuously tuned, so if we tune the microstructure properly and then measure the hardness and osmotic pressure of the gel that emerges, we can connect the micro and macro data.

The data is connected, but I have been working with them to understand what kind of changes are behind the connection, and we are now beginning to understand what these changes are.

We are now at a point where we will have a rough idea of what to expect in a few more years.

I believe it was in this context that Dr. Sakai gave me a homework assignment, telling me not to be satisfied with such a place: "At ERATO, expand the science of gels into different fields.

Sakudo:I come from a different field and have been doing gel science using my previous knowledge, but the direction is relatively easier here.

The point is to bring in concepts that have not been introduced into gel science, so there are some difficulties, but it can be done.

Now, however, they want to bring what they have learned in gels to other fields.

I think this one is more difficult for me and quite challenging,

I would like to do that.

Sakudo:To briefly introduce my background, I am from Itami City, Hyogo Prefecture, and was in the Department of Chemistry for my master's degree and in the Department of Physics from my doctorate.

I originally did something other than polymers and went on to study chemical physics, quantum properties, quantum physics, and nuclear physics.

After leaving there, my career has been in soft matter, gels, and rubber research.

So you have transcended different fields.

Sakudo:I have done quite a wide range of work from particle physics to condensed matter physics before I started working on rubber and gels.

We have experience in a variety of methods, from large-scale numerical calculations using supercomputers to analytical calculations.

For example, in particle physics, I was working on what is called quark confinement.

For my dissertation research, I was working on stories related to so-called Bose-Einstein condensation and superconductivity.

Then I was doing basic research related to the law of increasing entropy, or chemical physics research, and so on.

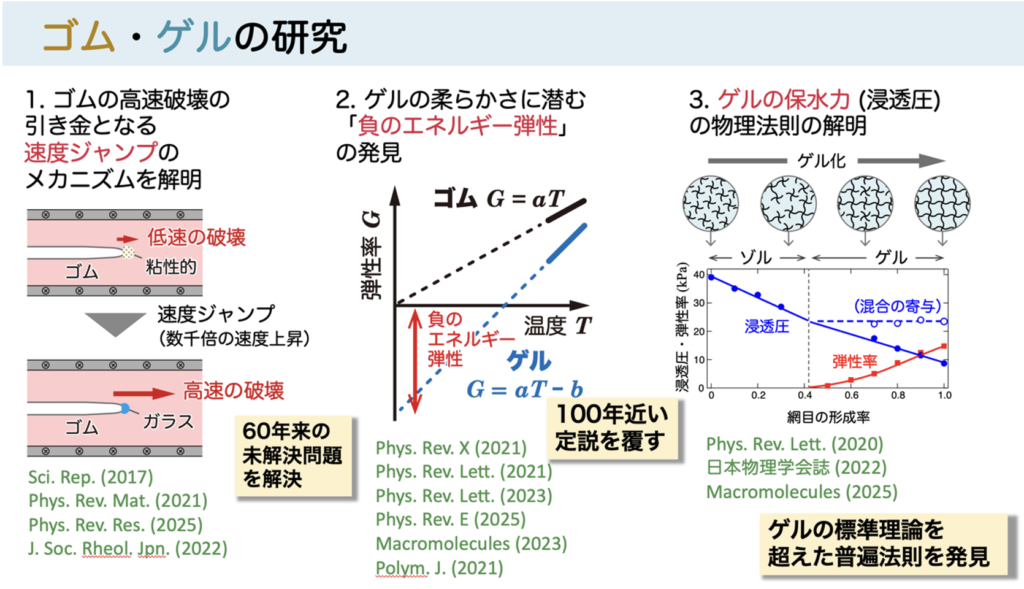

Sakudo:As for my research on rubber and gels, before coming to Sakai Lab, I was previously working at Ochanomizu University, doing research on rubber.

You have experienced the difficulty of tearing off a plastic bag from a supermarket even if you wanted to.

I was doing research related to this phenomenon.

Sakudo:Since it cannot be torn off, the cracks slowly develop, and at a certain point, they snap.

At this time, there are times when the cracks move slowly and other times when the cracks move quickly, but what triggers them was actually not well understood.

In this regard, we have clarified that a fairly simple model can explain this.

This has been a known phenomenon for about 60 years, but I think the explanation I found probably solved it.

Sakudo:The second is the elastic modulus of the gel, and this is where the research in the Sakai Lab begins.

Regarding the question of what determines the modulus of elasticity of a gel, the empirical common sense was that it is roughly determined by the entropic elasticity of the rubber elasticity quantity, just like rubber.

Actually, not only that, there is also a rather large negative energy elasticity effect, and I did research to clarify that the elastic modulus of the gel cannot be explained without using this effect.

After clarifying it experimentally, I clarified it theoretically on my side.

Sakudo:The third is the law concerning the osmotic pressure of gels.

It is known that the osmotic pressure of a gel gradually decreases as it solidifies, but the rules of how this decrease occurs were not fully understood.

We were also able to discover a fairly clear rule of thumb on this as well, which would be fine. These are the major tasks.

Sakudo:Based on these findings, I would like to consider various different fields and develop ERATO research in completely different fields, such as geophysics or space, for example.

Takahashi:Thank you very much.

Mr. Tanaka of RIKEN has also crossed many fields, hasn't he?

Tanaka:I am someone who has moved from the heart of engineering to biology and interface science, but have there been any discoveries or points that you have made by traveling in different fields, or points that you have gone beyond?

Sakudo:I think there are many levels, but first of all, when you switch fields, there is naturally some anxiety and difficulty, but I am the type of person who gets quite excited.

We need to rebuild our heads first.

And when I go, I go in feeling like a complete amateur because I really have something that I've built up before, but I know that if I bring it in, I'm going to fail.

In fact, since I was unknown, no one knew me at all when I went to academic conferences, and people looked at me like, "Who is this guy?

I think it is fun to be able to start as an amateur and gradually work my way up and eventually make a name for myself.

Tanaka:I think that gel is a concept that straddles different fields, and I am looking forward to today, thinking that I can be a new interface that connects various fields through gel.

Takahashi:I was extremely curious as to why Mr. Sakumichi chose gel from all the research he was doing on elementary particles and the high road of physics.

Earlier, Mr. Sakai mentioned that ger is like being in the peripheral area.

Why did you choose to study gels?

Sakudo:There is a lot to talk about this too, but I first got involved in rubber research through my work with Quantum and others.

While working with rubber, I knew that gel was a very similar substance, but I wanted to do rubber more than gel.

Why, because I am a physicist and I like simple things, and rubber is just a network, simple.

Sakudo:Gels, on the other hand, are networks + solvents.

I think gels are complicated because they have two elements, so I wanted to study a simpler rubber than that.

At that time, I happened to meet Mr. Sakai at an international conference in the Netherlands, and after chatting with him, I realized that GER might be simpler than I had expected.

For example, if you buy soba noodles from a convenience store, the soba noodles will be a little messy and difficult to eat.

When you buy soba, it comes with water, and if you pour the water over the soba, you can eat it easily.

In other words, the network can be unwound by adding solvents.

Sakudo:I'm a physicist, so this dilute network, when considered as a mathematical model, is a situation of a puka-puka network floating in a vacuum, a dilute network floating in a vacuum, which is rather easier to handle than a dense network.

I thought, "This is simpler," so I had no choice but to gel.

So I went to Ger.

Sakai:It was pretty quick.

So we became friends in Holland, and then maybe two months later.

Sakudo:Mr. Sakai asked me if I would like to come talk to him when I returned, so I went to see him, we talked, and he moved quickly.

Sakai;Tell them to come over to my place.

Sakudo:The sooner the better. Yes, I came to Sakai Lab with this feeling.

Takahashi:I see.

I have been making various new discoveries more and more, as Mr. Sakai introduced earlier.

With the introduction of Sakudo's theory into the mix, we are gradually beginning to see a system of gels that we had not been able to understand.

We are now at the stage where we are ready to move on from there.

Sakai:Yes, it is.

In those days, I am basically an experimentalist, so I do experiments.

Then, from the microscopic parameters, we can see that to some extent there is likely to be such a law, but it almost doesn't fit the textbook model.

So the model in the textbooks is almost always a lie, in GER's case.

Sakai:Then you end up with a paper that says not like this, not like that every time.

We will probably talk about a revision formula that looks something like this.

I thought it would be super cool if I could take it one step further and theorize the whole thing.

I'm not one to theorize with formulas, so I couldn't push through on my own, and that frustration has always been there.

Sakai:At that time, I happened to meet Mr. Sakudo in Holland, and I thought that I could become very strong if I played catch with him, so I asked him if he would be my catch partner.

Working with him, I was able to understand gel, of course, but through that, I was able to make contacts with more abstract things, such as the physics of strings and networks.

I kept wondering if it would be possible to develop the story into something a little more abstract, and that's how I came to this point.

Takahashi:Thank you for the valuable background story.

Now, to change the subject a little, when I understand the theory, I feel that jellies, or precision jellies, do not sound very tasty, but they may lead to new textures or even food science.

Sakai:Yes, it is.

Especially with food-based products, we are talking about water release.

When you open the film of the jelly, a little water comes out, right? That's it.

Sometimes the jelly goes down the back of the throat when you eat it.

That can cause aspiration when elderly people eat, so the problem of water separation is quite food critical.

Sakai:From our point of view, the balance between osmotic pressure and elasticity can be put into a mathematical equation.

With food, you know from intuition and experience that if you do this, it will turn out this way.

We can't make it permeate the world if that's all we do, so we prepare a formula and think about it.

There is a point that if it can be abstracted in a formula, it can be applied to the food field rather well, since it is sometimes a rule that all gels should follow.

If someone is doing something gel-like, I think we are getting very close to the point where our findings can be used.

Takahashi:It's going to change the way we cook and so on.

Sakai:It's going to change, and I want to do it.

Sakudo:Yes, it is.

To use an analogy, in sports, there used to be a lot of gut feeling, like practicing without drinking water or jumping the rabbit.

But as more and more scientific data is accumulated, it is possible to become stronger in a more rational way, and I think it is quite advanced in the West, but when you put science into it, it usually beats gut feeling.

Sakudo:Perhaps the same is true for food.

I think we can clarify some aspects of what may be a sort of gut feeling by simply using a little new gel science.

Designing Gels at Will

Takahashi:Thank you, Mr. Sakudo.

Now, let us hear from Mr. Masuda of the University of Tokyo.

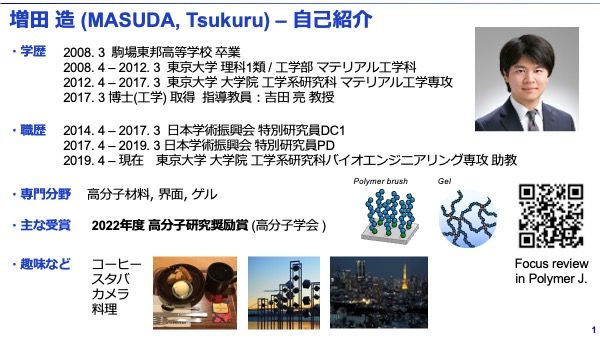

Masuda:Thank you for the introduction. My name is Masuda.

My affiliation is slightly different from Dr. Sakai's and Dr. Sakumichi's, but I am currently a faculty member of the Department of Bioengineering in the Graduate School of Engineering.

As for my background, I am actually from the same laboratory as Dr. Sakai.

I earned my degree in a place called Materials Engineering, and then became a researcher and then a faculty member.

Masuda:My specialty is polymeric materials, especially in chemistry and polymer chemistry.

To put it roughly, we are doing research to create a function by neatly synthesizing a very thin gel, a gel-like substance about the size of a nanometer.

I also wrote about my hobbies and interests. Now that you mentioned cooking, I like cooking as a regular hobby because cooking is similar to experimentation in some ways.

Masuda:Here is a little introduction to the research.

What is good about being able to do chemistry is that you can freely make anything you want to make, roughly anything you want to make.

Recent gel-related research includes the development of gels that adhere well to the skin, thin coating materials for medical materials, and the analysis of how proteins, cells, and other biological materials adhere to each other.

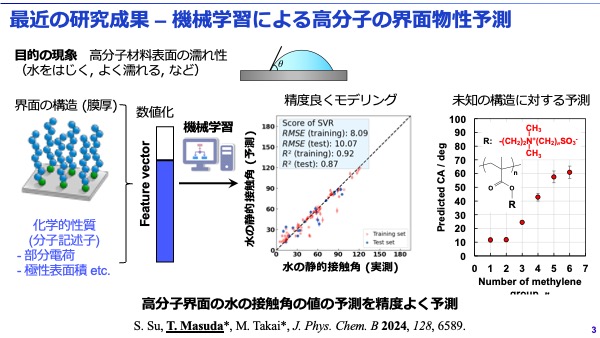

Masuda:I did say that it is okay to do anything, but recently I have been feeling more and more that I want to make something with a proper understanding of the law.

Recently, we have been using machine learning to create models that predict the properties of gels given parameters such as chemical structure and gel thickness.

Masuda:What I am particularly focusing on in what you are showing on this slide is the wetting of the water.

Masuda:Surface or interface is an important keyword. For example, it is said that to make a material that is easy to fit into the body, it should be like a material that fits in with water.

It is a phenomenon that is closely related to the removal of dirt in our daily lives.

We reported a model that can predict well from a state where the surface of the material is extremely easy to apply water to the surface to a point where the surface is smooth and water repellent.

Takahashi:Masuda-san mentioned film in your talk. Is it possible to precisely design film as well?

Can you control wettability if you can design it?

Masuda:I think we talked about brushes for a moment, but those can be really precisely configured.

I'm writing about polymers as if they were connected to each other, but you can really design how they are connected, what they are made from, and so on, at will.

Takahashi:Since you mentioned that machine learning can generally make predictions, does this mean that we are getting to the point where we can create products with a variety of functions if we adjust the way we formulate them properly?

Masuda:Yes, roughly speaking, that is the image.

If you input a chemical formula, the system will predict that it will have these properties.

New research areas arising from an understanding of the universal properties of gels

Takahashi:Hearing all this, I was already under the impression that the gel could be conquered.

Is it your goal for everyone to raise it to the point where it can be done more systematically?

Sakai:Yes, it is.

This still leaves us with a molecule, so we are thinking about anything networkable enough.

So the essence of gel is that it is a network.

Sakai:For example, in Masuda's example, there is a story about how changing the molecule changes the viscosity.

On the other hand, the hardness of a gel, for example, to put it in the simplest way, is the same no matter which molecule you use to make it, as long as the shape of the network is the same.

If you have a network of strings, and you start up a network around here roughly, it will be something like the elasticity of the network.

Once you get that level of abstraction, it doesn't have to be a molecule.

If it were a network, that's what we would be talking about.

Sakai:On the other hand, there are some network experiments that are difficult to do if you actually want to do them.

For example, you can't experiment with social networking sites to see how you can break the circle of people.

At any rate, everyone, like, please cross 10 people off your list of friends.

So it is not possible.

If it is gel, it can be cut to bash.

So, in the case of gel, it's like creating a network like any other network and actually testing it because you can actually experiment with it.

I am thinking that such an approach is possible.

Takahashi:This is a new approach to sociology, not just theory or chemistry, but also sociology and a wide range of other fields, and it is an effort to take on the challenges of the future.

Sakudo:There are also some studies of earthquake models.

I actually gave an online lecture some years ago on a talk about gels, because of the Corona disaster, and the audience was over 100 people.

One of the participating students e-mailed me and told me that he was interested in my research, so we talked a little on the zoom and I told him that I wanted to do research on earthquakes and the like.

And I said, well, come to my house.

I told him that if he wanted to work on earthquakes, he could use the gel to study earthquakes, and he agreed to go.

Sakudo:I'm in my first year of my master's degree and will be in my second year of my next (April 2025) doctorate, and I'm steadily advancing to do research on earthquakes in Ger.

We are doing cycles related to earthquakes, such as gel fracture and visualization of elastic waves in gels, and we are finally at the stage where we can really simulate an earthquake with gels in a few more days.

Takahashi:The centripetal force of the people around Mr. Sakai and the fact that they are willing to come to our company and conduct experiments is also amazing.

Sakai:Sakudo-san often brings quite a few students with him.

Sakudo:I've been through a lot.

Good people apply, and we say, "Well, come to our house," and there are many such people.

There are three people from different fields coming to the lab this coming April, and I have been talking to all three of them.

Takahashi:Thank you. It has expanded into a discussion about solicitation, hasn't it? (Laughter)

Application to Biological Tissues

Takahashi:Now, next, can we have Mr. Tanaka from RIKEN?

Mr. Tanaka is not a member of the ERATO team, but I invited him to this meeting because I thought he would have a good feeling with the complex gel project on my side.

Tanaka:I have a mechanical engineering background and originally entered a technical college of technology to build robots with the ambition of participating in NHK's robot contest.

Tanaka:When I thought I had not had much to do with gels, using metal or stiff materials, I began to receive offers to measure skin hardness or to do regenerative medicine.

There was a time when the idea of medical-engineering collaboration was popular, and I was involved in research on what could be done by applying mechanical knowledge to medical care.

From there, my research interests expanded to include proteins, cells, and biology.

Tanaka:Recently, AI and robots have become more accessible, and we are also working to automate experiments, for example.

The newer ones are getting to the point of using robots to sample and analyze the metabolism taking place in plants.

As you can see in the middle of the slide, we have succeeded for the first time in the world in measuring the wettability of cells and biological tissue surfaces, which is the closest thing to gel. I am also working with various gel material researchers.

Tanaka:Since you mentioned that everything is gel, let me reflect on this for a moment.

This is the earliest foot robot, which I think is made of metal, but the part that absorbs shock is actually a polyurethane elastomer, a porous material.

I was listening to the talk, thinking that it would have been helpful if I had had a precise theory at that time, because by changing the degree of porosity, it was possible to absorb shocks well and add various functionalities.

Tanaka:If you are interested, please feel free to search for us.

So I remembered it as if I was actually quite involved in gel research.

Sakai:Yes, it is.

You are gerging a lot.

Elastic sensing is a gel, he said.

Also, cell sheets are gel.

Tanaka:Exactly.

Also, now there are organoids and self-organization, which is an interesting phenomenon in which cells themselves self-organize into networks, so I think I heard a good story.

Please let me learn from you all in various ways.

Takahashi:Mr. Tanaka mentioned skin in his talk, and I thought that if we could theoretically view skin conditions in the context of gel research, our approach to skin would change.

Have you and Mr. Sakai started any initiatives?

Sakai:I see.

Basically, skin is exactly what it says there, viscoelastic material.

An elastic object will want to return when pushed and will try to return with a slight delay.

Viscoelastic substances have a kind of viscosity that absorbs it.

Sakai:Viscoelastic materials include rubber and plastics, but there is not yet a group of materials with precisely tuned viscoelasticity.

I think that if we had that, we would be able to do a lot more research, but we don't have such a thing, and we need to create such a group of substances.

I have been systematically creating and researching, and although I am now focusing more on elasticity, I still do not have a proper understanding of the viscoelastic part.

We were just talking separately about how we would like to start with manufacturing and then work on precision measurement.

Takahashi:Can you make something skin-like with gel?

Sakai:Yes, I think so. If you aim to make it, you can probably do it.

Takahashi:Do they still exist in practice?

Sakai:Dr. Furukawa of Yamagata University did that, didn't he?

You measure the baby's cheeks.

Sakudo:I thought that if we actually brought the baby in and measured the baby's cheeks, we could make a gel with an elastic modulus about the same as that of the baby's cheeks.

Takahashi:In the case of skin, there are several layers, such as the surface layer of the skin and the dermis, which is a little deeper. I thought that if we could create these layers, it would lead to a deeper understanding of the body through gels.

Sakai:Yes, we are talking about using a 3D printer to make gels together to do research in that area.

In the earthquake story I mentioned earlier, I would like to eventually use a printer to make all the plate-like things and do some skinny-dipping research.

Printers that can make such models, like 3D printers, will be a key technology in advancing what we have talked about here in the future.

The New World of Gel Science

Takahashi:This is exactly what I mean by the world of gels expanding through the fusion of various types of knowledge.

Now, I would like to ask for your thoughts on how the world view will change in the future.

Sakai:Yes, I would be glad to have Mr. Sakudo talk about this. While Mr. Sakumichi is thinking about it, let me tell you a little about it.

Originally, there was a polymer gel research group (Gel Research Group) within the Society of Polymer Science, Japan.

The Gel Research Group was originally started by people working on gel research, but people working on polymeric micelles and nano-assemblies, for example, also come to the group.

The polymer brushes and nano-assemblies that Masuda-kun is working on are not gels, but in the end, they are determined by the balance of osmotic pressure and elasticity, so there is a culture of broad acceptance that they should be gels.

I don't know if it's because Ger people are still minor, but they always go looking for Ger-ness.

That's gel, like okay.

Sakai:I've been in the industry since I was about 20 years old, and, well, there's a part of me that says, well, that's fine with Ger, because it's this way and that way.

Gel is a substance, but it is also a state.

Rubber, natural rubber, for example, will give off juice when the wood is cut.

This juice contains the macromolecules from which rubber is made.

When sulfur is added to the juice, a reaction occurs that cross-links the polymers that make up the rubber and solidifies them into a network.

When it solidifies, generally it is solidification, but what can I say, we refer to the state and say it is gelatinized.

Gel is both a substance and a state, after all.

Gel is a concept that can encompass a variety of things in many different ways, and there is no end to it.

I bought enough time. (Laughter)

Sakai:And slime. The slime.

That's not exactly a gel, either.

To be precise, that is a liquid because it flows.

It can be said that it is a very thick liquid, but if you look at it for a second or so, it behaves like a gel.

Then I can say, "If the range is about 1 second, it's gel," or something like that.

Really, really.

Even agar is not really a gel.

Takahashi:Not gel?

Sakai:It took about a year for that one to change shape, too. Actually.

In truth, it is not a gel, but of course we think it is.

It can wait a year, and if you wait a year, that's right, but you can't wait a year, so we perceive that as a normal gel.

So if someone couldn't wait a year, that would be a gel now.

That's how I see it. Ger is originally quite broad in its thinking, and it's a very broad view of the world.

I think the core of this project is to see what would happen if we took what we used to do just for fun and made it into something serious.

Takahashi:Now that Mr. Sakai has made time for us, please let's hear from Mr. Sakumichi. (Laughter)

Sakudo:The first thing I would like to say is that when I think about why gel science is so hot right now, I believe that one of the factors behind the rapid progress of gel science, which has to some extent come to a standstill, is precision synthesis.

As Masuda-san mentioned, when it became possible to design molecules in a clean manner and create a clean network structure, it was a major discovery that it became possible to fine-tune the microstructure of heterogeneous materials that do not have a clean crystalline structure, such as gels, glasses, and powder aggregates. I think it is a great discovery that we can now fine-tune materials that do not have a clean crystalline structure, such as glass or powder aggregates, from a fairly microscopic structure.

Sakudo:When this happens, macroscopic materials can be created with a good understanding of the microscopic structure.

In terms of a new world view, I believe that there will be a major update in terms of the ability to use various materials as gels through the combination of microstructure and macroscopic physical properties.

Takahashi:This may change the way chemical and food manufacturers think about manufacturing.

That might be a possibility.

Sakai:That is exactly what I think.

I still think that abstraction is the key point.

Gel is taken in the abstract.

Sakai:Abstraction may sound like a blur, but it actually leads to a proper extraction of the essence and understanding of the essential structure.

I think we are at a point in time where we are beginning to understand the essence of gel and have abstracted it, and we can analyze food products as gel, and there is a possibility that we can take a more different aspect.

Takahashi:Yes, thank you.

In no time at all, it was already time to go.

Today, I have presented a new view of the world of GER and other aspects of GER that are a little different from what the audience has been expecting.

Finally, I would like to ask each of the speakers to say something about what kind of people they would like to see in GER, and I would also like to ask Mr. Tanaka to comment on how he would like to see GER involved.

I would like to start with Mr. Tanaka's talk first, if that is correct.

Tanaka:What I expect from gel science is that, since I am a life science researcher, I think that plants are exactly like gels, and that the concept of gel can also be used to describe soil.

So I would be really happy if there are any developments in global or world-scale phenomena, and I would be grateful if they are relevant to our research as well.

In terms of human beings and life, it would be very interesting to see how the introduction of gels could provide new functions to our ears.

I thought it would be interesting to create a non-contiguous life form.

Takahashi:Thank you, Mr. Tanaka.

If you have any suggestions for people you would like to see enter the ger world, I would like to hear them from Masuda-san.

Masuda:In the field of gels, there are people like Mr. Sakumichi who are physicists, and I am more of a chemist, but I think it is great that there are people like both.

When creating a single object, physics is more about the laws that do not depend on matter.

Chemistry, on the other hand, values the individuality of matter.

It's pretty much the opposite of the route.

I would like to do my best to go beyond the opposite and hope that such a world view will develop through gel science, where physics and chemistry really become one.

Takahashi:Thank you, Mr. Masuda.

Now, Mr. Sakudo, please.

Sakudo:I think the good thing about the GER is that it is relatively open to newcomers like myself, and it is also OK to take on something else after starting at the GER, so the metabolism is quite high.

What I want to say is that in terms of human resources, the field of gel should be open first, and if you think you have some connection with gel, you can come.

I feel that we should have a discussion first, and if we can make a connection, we will work together.

I think that as long as the mind is open when it comes to engaging about GER, that is good enough.

Takahashi:I would like to conclude with Mr. Sakai's suggestion that the concept of gel could be expanded if we could also engage with people in the humanities and sociology from perspectives slightly different from those of science and engineering.

Sakai:Oh, it's a difficult pretense.

For example, I think there are quite a few fields in the humanities and sociology, such as systematization, parameters, etc., that probably also have an engineering aspect to them.

Even in the engineering department, when we actually do such things, we talk to people in the humanities and social sciences, and those slots are becoming more and more common.

Various structures are generally networks, so there is a pretty common language.

So, I think these people would probably join us in this kind of abstracted gel, and we would probably be able to speak the same language.

That is the kind of person I would like to see enter the program.

Sakai:I know there are a lot of companies out there, but there probably aren't many companies that gel.

It's quite common in food companies, but it's just that it's quite common that someone in one part of the company is doing the gelling, and many people are quite annoyed by it.

Because, there are quite a few people who are made to do it because they are in the chemical field and you can do it anyway.

It's impossible. It is quite difficult.

That's the one who, like Masuda you said, should know something about chemistry and physics and both gels somewhat to some extent.

We really hope that these people will come to GER, communicate with us, and bring back GER's knowledge.

We will always find what makes GER unique, so I hope you will not be afraid to come to GER.

Takahashi:Yes, thank you very much.

Among the things you mentioned today, we have learned that things that were previously undiscovered in the world are now being revealed in Japan.

I felt that it was a great time to be in a situation where I could immediately work with people who are active in such fields.

I hope that we can work together with everyone in the audience today to create a new field of gel research and a new world view, and that we can do more from Japan in this area.

I believe that everyone who has listened today is a fellow GER member, so let's create research together.

Thank you for your time today.

Please give a round of applause to the speakers.

Thank you very much.

The Sakai Complex Gel Project website isthis way (direction close to the speaker or towards the speaker)